📍 South Korea 🇰🇷

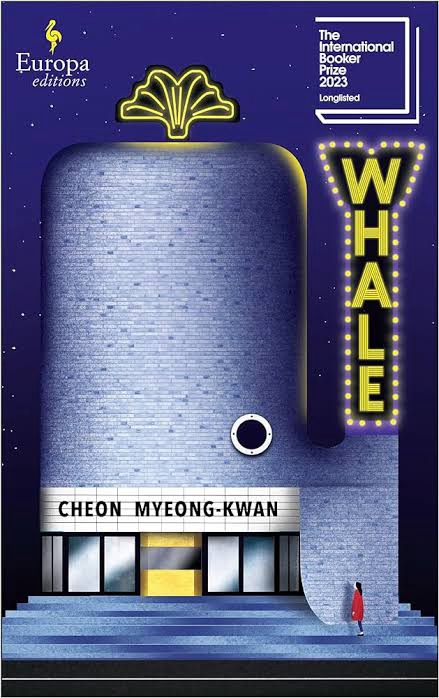

Geumbok is an extraordinarily fierce and courageous woman who is set out to expand her life, to bring enormity in all its glory and forms into her life, so that she can regale in its obscenity. As a child, she sees a whale and gets enamoured by it. The whale becomes an inspiration for her to dream big, to pursue and achieve impossible things, especially things that are deemed undoable by a woman. She runs away from her small village, comes to the Wharf, meets the fishmonger with whom she starts a fish drying business. There she encounters Geokjeong, falls in love with him, marries him and later realises his stupidity and inherent violent tendencies. Catastrophes befall her in continuum that leads her to a nondescript village, Pyeongdae. Here, she becomes the talk of the town, builds a cafe, starts a brick making business and opens a movie theatre designed as a whale. She becomes rich, arrogant and doesn’t predict the unfortunate destiny that is awaiting her, which true be told, had always been encircling her.

Chunhui, is Geumbok’s mute daughter, forgotten by the mother and the people around her. It’s her enormous size that gets people’s attention but soon their interest wades away because of her inability to communicate and comprehend. But she does possess a magical ability to talk to elephants and Jumbo becomes her only confidante. She learns to make bricks, adores daisy fleabanes and forever wonders why the world is the way it is. She becomes a suspect in a disaster that destroys Pyeongdae, gets incarcerated, undergoes unimaginable torture in the prison and is released after many years. She goes back to the ramshackle city only to find it in ruins. She then goes on to lead an absolutely lonely, marooned life making bricks.

There are hoards of interesting characters in the book like the one eyed woman, the old crone, the twins, Mun, Ladybug etc who bring their own whimsy, quirks and terror to the narrative. Pathos and grief await at every turn for all of these characters. Despondency and mayhem form the hallmarks of the plot. However, despite the grotesque events that make you squirm and your skin crawl, the ingenuity of the writing is such that it succeeds in keeping you hooked.

Whale, shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, is a story like no other. Even if I try my best, I wouldn’t be able to classify its genre or its style. To say it is unique would be a literary disservice. It’s a story that has history, folklore, magical realism, dark humour and feminism. The narrative for two thirds of the book is fast paced while the remaining third assumes a relaxed tone. The words are full of vivid imagery. They convey innocence, violence, hatred, longing, iniquity and doom. At the same time they also bring about revulsion by depicting bodily fluids, diseases and putrefaction. Sex finds liberal mention through the pages and the author doesn’t shy away from being graphic, problematic and harsh about it.

Geumbok’s character is one that is going to stay with me for a long time. She is multilayered, multifaceted and multitalented. She’s sexual and owns her sexuality. She resists every patriarchal norm and challenges everyone’s, including the readers, innate prejudices and chauvinism through her beguilingly subtle and brutally grandiose ways. She represents liberality and makes us question stereotypes. She’s selfish in her wants, selfless about her prowess. She’s flawed, witty, promiscuous, odious,mysterious and extremely narcissistic. There’s no one like Geumbok.

Though Geumbok grabs our attention, Chunhui asserts her presence with her silence. In silence, she finds her strength too. She epitomises resilience and perseverance. Often times, characters like Chunhui dont find mention in books and media, let alone be the protagonist, but in this book, the author has projected the boredom and mundanity of Chunhui to be purposeful leading to an awe inspiring but lugubrious climax.

The author, Cheon Myeong-kwan, is a South Korean author, screenwriter and film director. This book has been translated into English by Chi-Young Kim who has done an incredible job in translating this phenomenal piece of Korean literature. Whale comes across as an astonishing feminist literature where women drive the story and men play second fiddle to them. Feminism, in this book doesn’t make men hapless and victimised, rather it asserts itself as being deliberately provocative and intentional. There’s three more things that enrapture the narrative; fishes and their fishy smell, bricks and daisy fleabanes.

Read Whale. Today!

~ JUST A GAY BOY. 🤓