📍 Myanmar 🇲🇲

The Rohingya people are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who predominantly follow Islam from Arakan State (now known as Rakhine State) of Myanmar (formerly Burma). They claim they are indigenous to western Myanmar with a heritage of over a millennium. The Myanmar government considers the Rohingya as British colonial and postcolonial migrants from Chittagong in Bangladesh. In addition, the government also does not recognise the term “Rohingya” (officially banned the word on 29th March, 2014) and labels them Bengali, a term wielded as a tool of erasure. Significant minorities of the Rohingya practice Hinduism and Christianity. They have been described by the UN as one of the world’s least wanted minorities and some of the world’s most persecuted people. They are denied freedom of movement as well as the right to receive a higher education. They have been denied Burmese citizenship under the 1982 nationality law, rendering them stateless in the land they consider home.

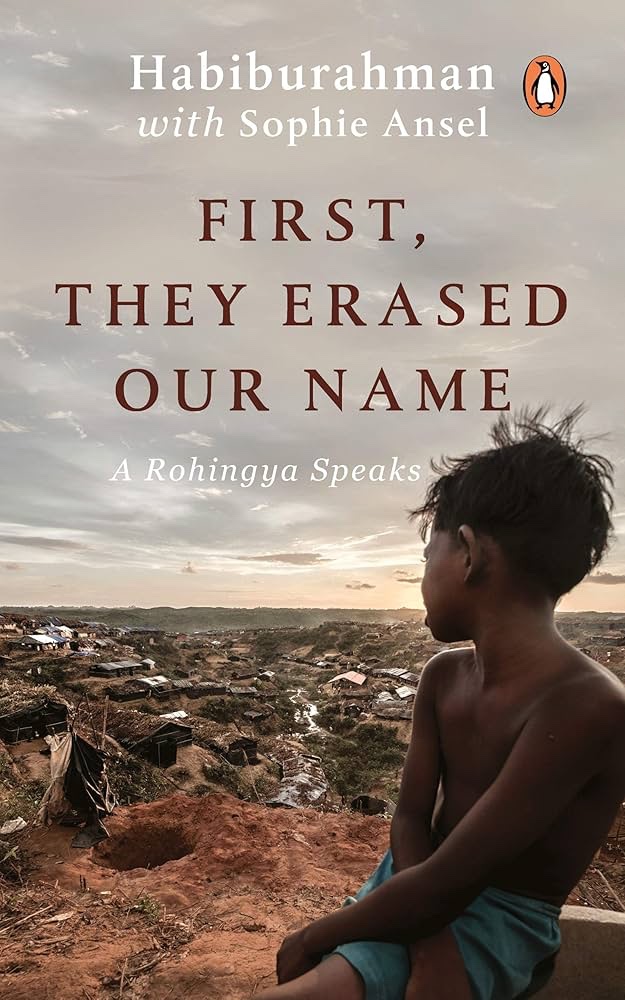

This memoir by the Rohingya author, Habiburahman, charts his arduous journey from being stateless in his own country to becoming a refugee across borders. He was born in 1979, in the Arakan state, in Western Burma. In 1982, under the dictatorship of U Ne Win, the Rohingyas were officially de-recognised as one of the Burmese ethnic groups. With that, more than a million Rohingyas were erased from the nation’s legal existence in an instant; and their history, culture and identity were invalidated. Even uttering the word “Rohingya” became forbidden.

The author describes growing up in the shadows of fear, exploitation, domination and relentless bullying. His parents taught him never to speak the word Rohingya for fear of violence from the authorities; Muslim was considered a marginally safer identity. He grew up knowing he was a criminal in the eyes of the state, someone whose very existence was a pretext for the military to bolster its authoritarianism and Buddhist ultranationalism. He describes how incredibly difficult it was for him to get an education because the schools and teachers belonged to the majoritarian community. Everyday life unfolded under surveillance and simple tasks were transformed into punishable acts.

Habiburahman recounts the constant racism he endured, how he was mocked and abused for his looks and skin tone thereby reflecting on the wider cruelty Rohingyas face simply for existing. All ancestral lands, including his family’s, were confiscated by the government and official documents were summarily dismissed. Children were barred from higher education. Crossing from one district to another required a maze of permissions, bribes and desperate pleading. Police detentions of both children and adults were routine, used as tools of extortion and intimidation. Those who could not pay remained imprisoned under brutal conditions for indefinite periods.

Against these insurmountable odds, Habiburahman remained determined to study law. Fully aware that leaving home might mean never returning, he risked everything to reach Yangon in pursuit of education. The journey, fraught with danger at every turn, only reinforced the reality that he and his community were considered the most unwanted people on the planet. However, as despair and the threat of imprisonment closed in, he made the agonising decision to flee Myanmar.

Becoming a refugee exposed him to new forms of danger in Thailand and Malaysia. Even with the help and recognition from the UN and UNHCR, he faced discrimination, rejection and statelessness in every country. Eventually, after encountering unimaginable obstacles, he managed to escape to Australia where dignity seemed momentarily within reach. Yet even there, citizenship remained elusive, his rights curtailed, and the label of a refugee clung to him. He realised, he would always be an outcast in the eyes of the world.

First, They Erased Our Name, coauthored by Sophie Ansel, translated from the French by Andrea Reece, is a searing and unflinching account of the brutality of the Rohingya genocide perpetrated by the Myanmar military junta. The world woke up to this act of ethnic cleansing only after an exodus of 600000 people landed at the Bangladesh border in August 2017. But as the book makes clear, the genocide has been decades in the making, enabled by state policies, discriminatory laws, and a hyper-nationalist propaganda that have incited massacres with impunity. The narrative also confronts Burmese politician, pro-democracy leader and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Aung San Suu Kyi’s reluctance and refusal, to address and challenge the genocide on global platforms. Instead, her silence, her deliberate omission to raise objection to this mass extermination, has rendered her complicit in this crime against humanity.

Habiburahman now lives in Melbourne. He founded the Australian Burmese Rohingya Organisation (ABRO) to advocate for his people back in Myanmar and for his community. He is also a translator, social worker and the secretary of the Arakan Rohingya National Assembly (ARNA), based in the UK. In 2019, he was made a Refugee Ambassador in Australia. Sophie Ansel is a French journalist, author and director who lived in South Asia for several years. She met Habiburahman in 2006 and has been advocating for their cause since 2011.

The Rohingya genocide remains an ongoing humanitarian catastrophe that has particularly intensified since 2017. It has led to mass killings, tens of thousands of genocidal rapes, destruction of villages and forced displacement of people and entire communities from Myanmar into neighbouring countries where they are forced to seek refuge. This crisis has created a fertile ground for human trafficking, where the perpetrators operate without accountability, while the victims die in obscurity or survive in the most inhumane conditions. The world has conveniently forgotten this calamity, just as it has forgotten the genocides and civil wars in East Turkestan, Tigray, Kurdistan and West Papua. According to the sources cited in the “Rohingya refugees in India” Wikipedia article, around 40,000 Rohingyas live in slums and detention camps across India, the majority of whom are undocumented. Under the Indian Law, they are considered illegal immigrants, and not refugees. They have been labelled as potential terrorists and are perceived as a national security threat leading to forced detentions and deportations.

First, They Erased Our Name, is a devastating read because it captures humanity at its worst. It is filled with details that are almost unbelievable. However, its chronology of events and descriptions that convey an apartheid, offer an invaluable lesson. The author, through his story, has shown how the human experience depends upon the geography, religion and appearance of a person and how when these conditions are not met, ostracism, slavery, violence and humiliation become the cornerstones of the same human experience. It forces us to confront a truth we repeatedly fail to absorb; nobody dreams of becoming a refugee or willingly chooses statelessness.

At its heart, this memoir is a reminder of our collective failure, our inability to protect the most vulnerable and our willingness to look away from ongoing genocides. It compels us to remember Fannie Lou Hamer’s words, which echo through every page of this memoir, ‘Nobody’s free until everybody’s free’. Habiburahman’s story is a testament to that truth and an indictment of a world that has yet to learn it.

~ JUST A GAY BOY. 😞