📍 Papua New Guinea 🇵🇬

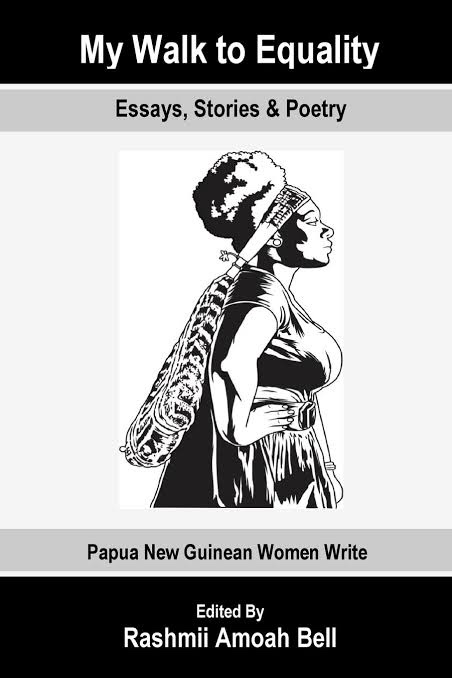

May is celebrated as the Pacific Islander Heritage Month and my pick this year was from Papua New Guinea (PNG). The book is an anthology of essays, poems and stories, written exclusively by Papua New Guinean women. There are more than 80 contributions from 40 writers, and the majority are in their 30s. For the uninitiated, PNG is a country located in Southwestern Pacific Ocean, occupying half of the island of New Guinea (the western half belongs to Indonesia). The country gained independence from Australia on September 16, 1975. It is one of the most rural countries and comprises of over 800 tribes. It’s also the most linguistically diverse country in the world, and about 839 languages are spoken in PNG. It also has the dubious distinction of having one of the highest rates of violence against women in the world. This book, therefore, captues the ongoing struggles of women who are trying to achieve a semblance of equality in a particularly patriarchal society.

The book has been divided into sections; Relationships, Self Awareness and Challenging gender roles and breaking glass ceilings. However, the overarching theme throughout is the demand for women’s rights and equality, the necessity to disband the deep rooted misogyny and the call for action against sexual and domestic violence. The writers boldly dissect the prevailing patriarchal culture in which young women are being brought up and how men are groomed to be sexist and gynophobic. The society at large is perverse to women being educated and taking up spaces in public and private sectors. Working women are often scorned at, receive no help at home and face uphill battles navigating professional environments. These courageous women writers, many of whom are teachers and working professionals, have urged PNG women to fight for their education and never to dismiss any opportunity that could guarantee financial independence, which can then pave the way for the upliftment of their collective consciousness and thus inspire future generations.

Rashmii Amoah Bell, who has edited this book, is a Papua New Guinean writer and editor renowned for her contributions to amplifying women’s voices in her country. From this book, a few writings stood out to me for their poignancy and simplicity yet relaying the angst, anguish and resilience. The Expectation of Marriage by Watna Mori explores how colonial past and intergenerational traumas shape the reality of PNG women; how the entirety of a woman in PNG has been reduced to her marital status and the writer wonders what happens to women who consciously decide to live outside this boxed existence. Betty Lovai writes in her essay, Papua New Guinean women in Leadership, the harsh truths about securing leadership roles as a woman in PNG and the governmental and societal inertia in bringing about any positive impact. In the story, On the hunt for a New Language in Papua New Guinea, Samantha Kusari, makes a case for languages that are dying across the country. In the search for a tokples (dialect), the writer gets introduced to another rare dialect, Akadou, and hence realises the rich legacy of a language that now has only three living people speaking it. In Walk to Equality in Education, Roslyn Tony, laments about the insurmountable hardships met by teachers and women principals in the field of education. Caroline Evari’s poem, Who are you to tell me it’s wrong, explores the possibility of an egalitarian household in PNG. The brilliant essay, The Inappropriate Cultural Appropriation of the Bilum by Elvina Ogil, articulates the perils of the harmful practice of such a cultural theft. She provides the nuances that make us ponder the consequences of a heritage hijack, that which can undermine and undervalue an entire civilisation. Tanya Zeriga-Alone, in her thought provoking essay, Which way Papua New Guinea? Look in the Mirror; presents an insider’s perspective on the current situation in the country and says, that the only way PNG can move forward towards ensuring equality and equity, is by disregarding mediocrity, respecting fellow citizens and local talents, and understanding the collective resilience shared by all the tribes of PNG.

Having read this book, I wonder if the conditions for Indian women are any different; rather how eerily similar are Indian and PNG women’s struggles. On the surface of it, we may seem to be a society where women have rights, but certainly there’s no equality yet. If you scratch this surface, you will notice uncomfortable truths and predatory practices of misogyny, chauvinism, sexism and violence deeply rooted and being disguised as appropriated and misplaced feminism. We may be into our 79th year of independence and the fastest growing economy in the world, but none of that or the current ubiquitous vermilion can hide the fact, that women in our country are unsafe, undervalued, excluded, oppressed (especially Dalit and tribal women) and marginalised.

~ JUST A GAY BOY. 🧐