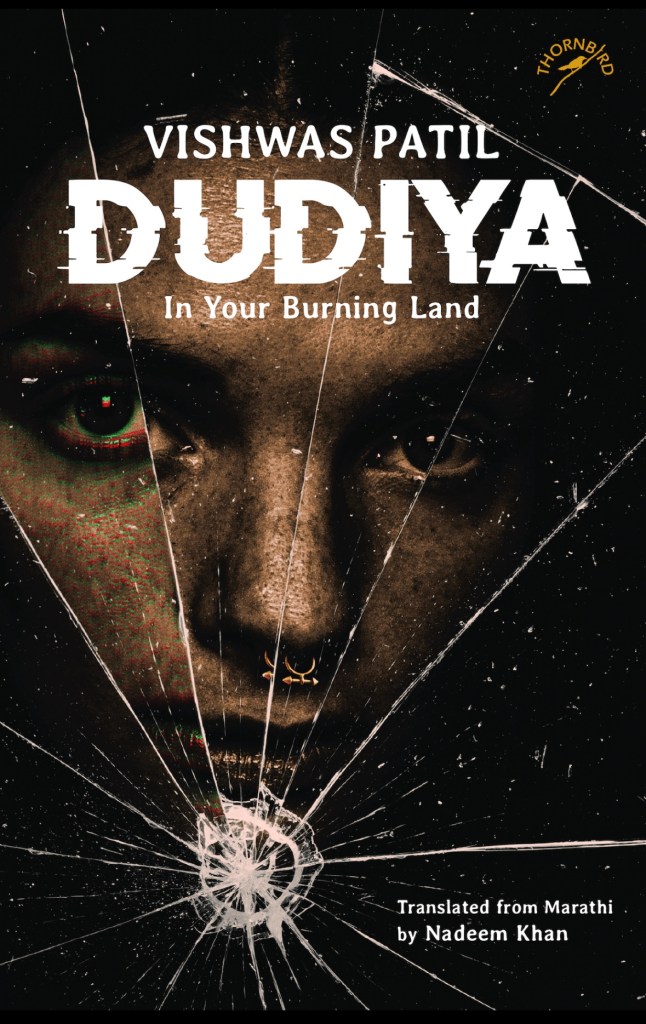

Read a Kitaab, reading community’s February month’s #readingindiachallenge was dedicated to Chhattisgarh and my pick was Vishwas Patil’s Dudiya. Written originally in Marathi and translated into English by Nadeem Khan, the book is a searing portrayal of life in the Naxal region of Chhattisgarh. The story begins in May 2013, when IAS officer Dilip Pawar gets posted as an Election Observer in the Naxal dominated districts of Chhattisgarh. His duty is to ensure smooth electoral process despite the grave circumstances of the region. His trepidation is put to test when he lands in the area and is inundated with stories of Naxal brutality and their ingenious ways in circumventing police surveillance and governmental interference. There, during his stay, he comes across this girl, Dudiya, who was born in one of the impoverished hamlets of Chhattisgarh, but soon joins the Naxals to escape the misogynist traditions and cultural norms of her village. During her training as a Naxalite, she soon realises how the original principles on which Naxalism was built have got eroded in the pursuit of establishing authority, control and hierarchy. Violence is commonplace and often misguided. Misogyny remains omnipresent in the Naxal camps though not as stark as in her village. She ditches the Naxals and joins the police as an informant and begins her life anew whilst trying to heal the traumas of her past.

Inspired by real life events, the book gives a thorough introduction to the region that has been plagued by the Naxalite movement. The author has on no occasion taken sides. He deftly portrays the history of the rise of Naxalism, its necessity, its spread and how its roots are linked to Maoism. Through various characters in the novel, he brings to light the politics that are deeply ingrained in the sustenance of the Naxal movement. Caught in the crossfire between the government and the rebels are the tribals of the region who have been completely forgotten by both parties. The apathy and ignorance of the political class in wanting to primarily weed out Naxal insurgents without addressing the grievances of the tribals at the grassroots level, exemplifies it. Through this book, the author has touched upon all of the above issues, without sounding patronising and being morally absolute.

Though the writing is simple and lucid, I felt it faltered at a few places when it tried to incorporate some element of ‘boob writing’ (the term, courtesy Daisy Rockwell). The description of the ‘bare breast’ tradition of the tribe and later of Dudiya’s relationship with an older man, bordered on titillation. Male writers should do away with these descriptions of women’s anatomy having lecherous overtones, because it serves no purpose in propelling the narrative.

Having said that, Dudiya is still a good book that attempts to provide a thorough understanding of the complexity of the Naxal movement. It also describes the lush yet difficult geography of the region. The author has given a vivid description of the Abujmarh forests, Tadmetla and Bastar. Vishwas Patil has done a fairly commendable job in bringing forth this national issue through the lives of the tribals who are easily dismissed in an often forgotten area of the country.

~ JUST A GAY BOY. 😐